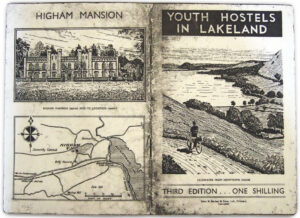

Higham is a grade II listed country house, built in 1828 by Thomas Alison Hoskins. It was designed in the Gothic Revival style which had been popular in Britain since the mid-18th century. It is laid out on a symmetrical plan and features towers with castellated turrets and arched Gothic windows. The north wing of the building incorporates a much earlier farmhouse called The High which already stood on the site. The architect is unknown.

Higham is mentioned in the architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner’s ‘Cumberland and Westmorland’ volume of his ‘Buildings of England’ series. His description is succinct:

“Gothic, probably of c.1800, a rarity in the county. Symmetrical, of eleven bays, with two tower features with angle-turrets set symmetrically. Pointed windows. Earlier building remains behind.” Higham’s interest to Pevsner lies in the fact that, as he notes in his introduction, it reflects the transition from one architectural style to another: “The picturesque enthusiasm was over, and Gothic went sensible.”

In 1775, Joseph Hoskins married Eleanor Senhouse, the daughter of a distinguished Cumbrian family, and as part of her marriage settlement the farm then known as ‘The High’ was given to the couple. When Eleanor and Joseph died in 1823 and 1826 respectively, their son Thomas Alison Hoskins (b.1800, Liverpool) decided to make his family home at The High. He married Sarah Irwin in 1827 and began to create what would become a grand country estate, incorporating the original vernacular farm buildings into a much larger manor house in the Gothic Revival style, and adopting the new name of Higham. Higham would be the home of the Hoskins family for 76 years.

Thomas Hoskins was already a successful entrepreneur when he began to build Higham. The greater part of his fortune was invested in railway shares and in the 1860s he became the chair of the company formed to build the Keswick to Cockermouth railway line, which opened in 1865. Hoskins also served as a magistrate and chairman of the Cockermouth bench for many years; he was a member of Cumberland County Council, held the office of High Sheriff of Cumberland in 1854 and was finally appointed Deputy-Lieutenant of the county. Hoskins retired from the magistracy in 1871 and died in 1886.

Three of his children survived him. Reginald, the youngest son, had moved away and pursued a career in the army. Higham was left to his eldest son George and daughter Mary Hoskins. Neither married and they both lived at Higham until their deaths. George became vicar of Setmurthy in 1868; it was he, soon after, who supervised extensive alterations to the church building – the main entrance moved to the western end, tower and belfry added – which created the church we see today. The elaborately carved pitch-pine panels that decorate the eastern end of the church were mostly Mary’s work. George was later made an Honorary Canon of Carlisle, Perpetual Curate of Wythop and Rural Dean of Cockermouth. Mary was also responsible for overhauling the ‘sanitary arrangements’ at Higham.

In 1882, George retired as vicar of Setmurthy and he and Mary set about trying to sell the estate. Higham appeared in auctioneers’ catalogues for 1895 and 1896 but the estate did not sell. George died in 1899; Mary in 1904, leaving the house and surrounding estate of over 900 acres to their younger brother Reginald. Following the Inland Revenue’s valuation of the estate, the house contents were sold at auction and the land and property, which included Bully House, High Barkhouse and Cragg Fell, were bought by Joseph Fisher, whose family had farmed in the area for more than two centuries.

Frances was a keen collector of shells and her collection is now held at Tullie (formerly Tullie House Museum) in Carlisle. Joseph had a family coat of arms drawn up and painted on the ceiling above the main staircase. Frances died in 1911 and Joseph in 1921.

The Higham Estate eventually passed to their eldest son George (b.1876), who was responsible for installing the stone balustrading on the terrace in the late 1930s; George and his sisters Laura and Elsie also continued to purchase land and property around the house, eventually adding Brathay Hill Farm and Low Barkhouse Farm to the Higham estate. It was during this period that Arthur Ransome, a friend of George’s second wife Rosaltha, and Evelyn Waugh, a friend of Alan Fisher (George’s son from his first marriage), visited Higham.

When George died in 1947, Higham was left to George’s sons Alan and Francis. They immediately offered the house and 6 acres of land to the Treasury to offset death duties.

The rest of the estate was purchased by Francis Fisher in 1986 after a prolonged period of family litigation. It remained in the Fisher family until 2021, when Higham Estate – comprising 6 properties, 979 acres of farmland, 178 acres of commercial woodland and the Eel Settings fishing beat on the River Derwent – was purchased by another local man, Malcolm Wilson OBE.

The house lay empty for 4 years after it passed to the Treasury until 1951, when it was handed over, free of charge, to the Youth Hostel Association. Bunkbeds were installed in the upstairs rooms to accommodate up to 100 guests. The house was too cold for the hostel to open all year round, so in the winter Higham became a social centre for the local area, hosting dancing and amateur dramatics. Higham was also a little too far away from the central Lake District fells for the keen youth-hostelling ramblers who travelled on public transport, so in 1955 the YHA sold Higham to Cumbria County Council for £7,500.

The county council then ran Higham as a boarding school for girls from 1956 to 1974, but Higham was not a comfortable place to stay. There were problems with heating, woodworm, wet rot and the water supply. In 1968, Her Majesty’s Inspectors visited and produced a damning report, concluding that “On both educational and financial grounds, it might be better to build a girls’ hostel at Ingwell (a similar special school for boys, near Whitehaven) and use the new teaching accommodation there to the full. Higham is increasingly appearing to be the wrong school in the wrong place.”

In 1971, the school governors resolved to recommend closure. The Director of Education for Cumbria, Gordon Bessey MBE, who had been instrumental in the purchase of Higham, announced that Higham would be used “to fulfil the need for residential courses for adult education with particular reference to the in-service training of teachers, tutors, lecturers, youth leaders and other officers of the Council…It is suggested that Higham be used not only as an adult residential centre but as a training centre for catering staff which will overcome the supply problem…This is a once-for-all opportunity of using this fine building and site for a purpose, the need for which will become more and more urgent as the years go by.”

Within a month of the school closing, Higham re-opened as a residential centre for adult education, re-named as Higham Hall. Peter Boulton replaced Gordon Bessey as Director of Education and appointed Peter Hadkins as warden. Hadkins began to build relations with other adult education centres across the county, and with Newcastle and Liverpool universities, to diversify and expand the courses and summer schools offered at Higham. More alterations were needed to turn the dormitories into individual bedrooms and a residents’ bar opened in 1975. As Hadkins wrote, “Buildings that are 150 years old inevitably need a good deal of attention, and the Gothic Revival period was not noted for the soundness of its buildings. Numerous beams and plaster ceilings have had to be replaced; the stone entrance porch proved to have no foundations and had to be underpinned; it was rather alarming to discover that the insulation material used above the ground-floor ceilings was sawdust. There has been much to do outside the house as well. Undergrowth was cut back, paths re-laid and lawns trimmed down to size. A putting green was created on the lawn on the south side of the house. The pond beyond had become a stagnant marsh and had to be thoroughly cleaned out. At the back of the house the girls’ playground, which they had used chiefly for netball, was re-surfaced and transformed into an all-weather tennis court.”

The college went from strength to strength, establishing a reputation for both excellent educational opportunities, which included off-campus study trips to Norway, Italy, France, Russia and Egypt – and its catering. High profile cultural figures from Cumbria and beyond came to speak or teach at Higham: from Patrick Moore to Melvyn Bragg and Norman Nicholson – who gave his very last poetry reading at Higham – and local mountaineering legends Chris Bonnington and Doug Scott.

This final incarnation seemed to suit Higham. As one student wrote,

“Nestled leisurely in the rich, tree-lined, sheep-filled, water-softened Lake District is an old, mellowed manor house, creaking with historic sounds that bounce from the grey local stone, the spacious interior ceilings, and the secluded hallways that stretch through the floors like the long, linear antique fingers of a piano virtuoso. Higham Hall is no ordinary manor house; it is the site for residential courses provided by the Cumbria Education Committee…”

Alasdair Galbraith became the first college principal in 1991. Between 1991 and 2001 he oversaw many improvements to the accommodation (and bathrooms), and the commissioning of the commemorative stained-glass window over the stairs and the millennium tapestry which hangs in the dining room. Alasdair handed over the baton to Alex Alexandre in 2001.

As Alex recalls, he began to prepare the college for independence from the start; so, when Cumbria County Council announced it was considering the sale of Higham Hall in 2006, he had a plan. With the support of the Friends of Higham and a group of ‘trustees-in-waiting’ a business plan was developed, a charitable trust established to negotiate the purchase and eventually run the college, and a reserve fund created through the sale of over 3,500 ‘bonds’ at £25 each. This was students’ money, held in trust, to be spent on future courses.

After two years of negotiations, Higham Hall College became a company limited by guarantee, a registered charity and an educational trust. A 22-year mortgage was agreed with the Cumberland Building Society and the trust became the owners of the Hall and all its contents. All staff contracts were transferred across, catering and cleaning were brought in-house, and the transition from local authority to the independent educational trust which continues to run the college today was complete.

By the time Alex stepped down, the range of courses on offer had expanded further, as had the college’s art collection. George Cooke took over in 2012 and oversaw a period of steady growth until the world turned upside-down in 2020. His brinkmanship, with the support of the college trustees and a team of dedicated staff, steered the college safely through three very difficult years during the COVID-19 pandemic. When the college’s fifth principal, Dr Lizzie Fisher, arrived in September 2023, the college was facing yet more stormy weather as the cost-of-living crisis sent costs skywards at unprecedented rates.

A fundraising campaign is now underway and the Friends of Higham relaunched with the aim of rebuilding the college’s reserves, protecting and preserving our 200-year-old building and continuing to improve and invest in the site, teaching facilities and accommodation to ensure Higham remains a place that nurtures creativity, curiosity and wellbeing for generations to come.

In 2026 we will celebrate 50 years of adult education at Higham: 50 years of, in Alex Alexandre’s words, “enriching life in the broadest sense, providing opportunities to extend understanding, exchange ideas, develop skills and enjoy the experience of discovery.”

If the last fifty years have shown us anything, it is that the college is a living institution that has adapted and thrived and will no doubt continue to evolve to meet the challenges ahead.